Identifying clauses, especially dependent clauses, can be challenging. Try identifying all dependent and independent clauses in these sentences.

I could not complete the assignment because of a four-hour power outage.

Who attended the school I did?

If you go after anybody who owned enslaved people or belonged to an organization that was supremacist, then you have to change the name of the Carnegie library. The Washington Post

Whereas all three have one independent clause each, the first has no dependent clause, the second has one dependent clause, and the third has three dependent clauses. In this post, we’ll learn, step-wise, how to identify clauses in a way that you would be able to identify them in sentences from real pieces of writing like the third one. We’ll take up the above examples again later in the post, where you can see them dissected.

In this post, we’ll confine to identification of dependent and independent clauses, with practice exercise in the end where sentences have been dissected into their constituent clauses. We won’t go a step further to identify a dependent clause as noun, relative, or adverb clause. That’s a topic that requires even more depth and has been covered separately. Learn more:

Once you’re comfortable with identifying dependent clauses, you can start seeing them apart as three different clauses.

Let’s start with dependent clauses as they’re more challenging to identify.

How to identify a dependent clause?

A dependent clause is a group of words that contains both subject and finite verb (also called tense verb or main verb). A dependent clause does not represent a complete idea and hence can’t stand on its own as a sentence. Therefore, it’ll always come attached to an independent clause.

There are two ways to identify a dependent clause in a sentence. You can adopt whichever comes easy to you.

1. Start with identifying finite verbs

Every finite verb in a sentence is part of a clause. If you can identify finite verbs that are part of independent clauses, you’ll be left with finite verbs that are part of dependent clauses. This sentence, for example, contains two finite verbs – are bent and indicate.

Straws which aren’t bent in any direction indicate absence of wind.

Straws indicate absence of wind is a complete idea and hence the independent clause, implying that are bent is associated with a dependent clause.

After identifying the verb of the dependent clause, look for the group of words that start with certain marker words and contains this verb. (More on marker words in the second method.) Such group of words will be the dependent clause. In the above sentence, the marker word which starts the group of words which aren’t bent in any direction that contains are bent. Hence, which aren’t bent in any direction is the dependent clause in the sentence.

Let’s take another example.

I love pizza, but I rarely eat it because it is unhealthy.

The above sentence contains three finite verbs – love, eat, and is. Of these, love and eat are part of independent clauses. (The sentence contains two independent clauses, which is indicated by the coordinating conjunction but.) The remaining finite verb, is, is part of the group of words because it is unhealthy started by the marker word because. Hence, because it is unhealthy is the dependent clause in the sentence.

How do you decide the boundaries of a dependent clause?

Marker words make locating the start of a dependent clause easy. After that, you’ve to look at a self-contained unit or chunk. If it’s not intuitive to you, then understanding the role of noun, relative, and adverb clauses in sentences and their patterns will help. Refer to the links of each type of clause in the next method for details in this regard.

2. Start with identifying marker words

A reliable signal for the presence of a dependent clause is one of the marker words that start a dependent clause.

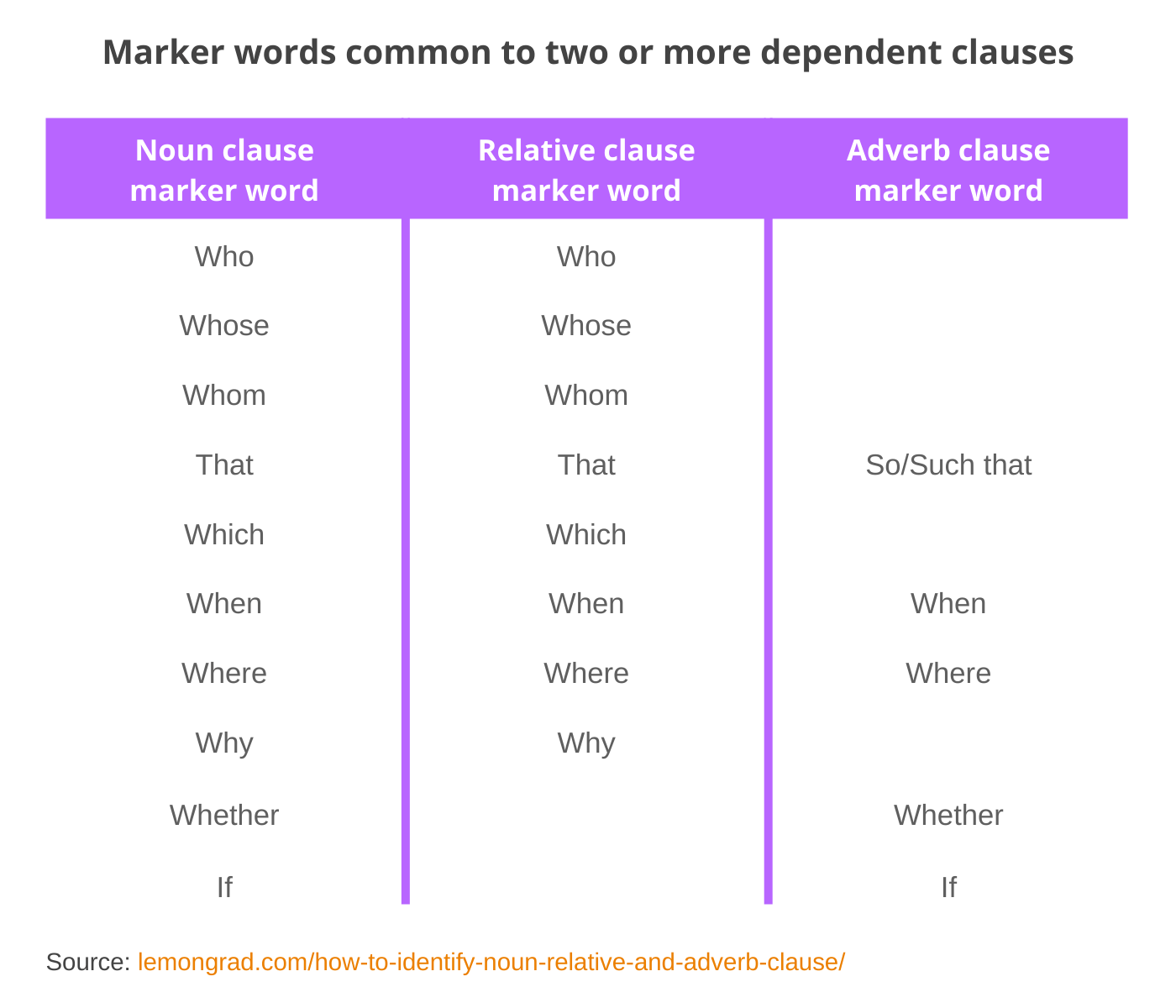

Common marker words that start a noun clause are that, how, if, what, when, where, why, who, whom, whose, whether, and which. And somewhat less common are whoever, whomever, whatever, wherever, whenever, whichever, and however.

Marker words that start a relative clause are who, whom, whose, that, which, when, where, and why.

The list of marker words that start adverb clause is much longer. The common ones are before, after, as, since, because, whether, if, as soon as, when, where, until, unless, whenever, wherever, so that, although, even though, while, and whereas.

If you noticed, few marker words are common in the above lists. Here is a handy list of marker words that are common to two or even all three dependent clauses.

To use the above image, cite the link in the button below (click to copy):

https://lemongrad.com/how-to-identify-noun-relative-and-adverb-clause/

If you see one of these marker words in a sentence, you should suspect that the group of words started by the marker word is a dependent clause and then confirm by locating a finite verb in the group of words. These sentences, for example, contain the marker words which and because, indicating the possibility of a dependent clause.

Straws which aren’t bent in any direction indicate absence of wind.

I love pizza, but I rarely eat it because it is unhealthy.

If we look at the group of words starting with these marker words, we indeed find the finite verbs are bent and is, implying that the two group of words indeed are dependent clauses.

But we haven’t accounted for the subject

Doesn’t the definition of a dependent clause say that it should have both subject and verb? The subject doesn’t figure in any of the two methods we looked at.

Every finite verb in a sentence is part of a clause, which could be dependent or independent. This fact along with the marker word allowed us to identify the dependent clause. All the dependent clauses so identified will contain a subject as well, but finding it is a mere formality. The dependent clause is already identified.

But if you need to identify the subject for sake of completion, you can. Identifying subject though can be tricky. Sometimes, like in the first sentence we saw earlier, the marker word itself is the subject, and sometimes, like in the second sentence, a regular noun or pronoun is the subject.

A simple way is to see if the marker word is followed by a noun or pronoun. If it is, then the noun or pronoun is the subject. If it’s not, then the marker word is the subject. In the first sentence, for example, which isn’t followed by a noun or pronoun, and hence which itself is the subject of the clause. In the second, because is followed by the pronoun it, and hence it is the subject of the clause. This will work mostly but not always. Learn more:

If you’re a beginner, the above process may sound somewhat daunting. But with practice, you’ll be able to perform both the methods together in a flash. The key is to get a feel of marker words, to become adept at seeing finite verbs, and to keep in mind few atypical cases, which takes us to the next part.

You may come across few atypical cases which may look like a dependent clause but are not. You may also come across few cases which may not look like a dependent clause but are. Develop an eye for them. The most common ones are.

Problem #1: Group of words started by marker words may not have both subject and verb

Don’t assume that a group of words started by a marker word will contain both subject and verb. These, for example, don’t contain subject-verb combination.

I know when to ask questions. [to ask is not a finite verb.]

I prepared my speech while having tea during the break. [having is not finite verb. While I was having tea would have both subject and verb.]

I could not complete the assignment because of a four-hour power outage. [Note that because of is a preposition. Because there was a four-hour power outage would have both subject and verb.]

How to check Covid symptoms and what to do if found positive are commonly asked questions by people. [There are potentially three clauses: don’t forget if found positive. All three verbs – to check, to do, and found – are non-finite though.]

Hence, above are all phrases – and not clauses.

In these examples, the marker word that is not even starting a group of words. It’s a standalone word referring to something.

That damage will be tough to repair.

We did that on purpose.

For the grammatically inclined, that is functioning as a determiner in the first sentence and as a pronoun in the second.

Problem #2: Marker words are different from question words

Many marker words, especially those belonging to noun and relative clause, are same as words that start interrogative sentences, which may lead some to mistake questions for dependent clauses. Most confusion occurs in case of noun clauses, where almost all marker words coincide with questions words and where the dependent clause can begin a sentence.

But marker words are different from question words. Here is a simple way to see if a sentence is a declarative sentence starting with a dependent clause or an interrogative sentence.

In a declarative sentence starting with a dependent clause, subject of the clause usually comes before the verb. In an interrogative sentence, subject of the sentence usually comes after an auxiliary verb.

How he got such awesome marks is beyond my understanding. [Declarative sentence starting with a dependent clause. Subject of the dependent clause, he, comes before the verb, got.]

How did he get such awesome marks? [Interrogative sentence. Subject of the sentence, he, comes after the auxiliary verb, did.]

What happens to the project is not my concern. [Declarative sentence starting with a dependent clause]

What will happen to the project? [Interrogative sentence]

However, this may not always happen. In this sentence, for example, the noun clause and the question are exactly the same.

Who is behind the mischief is known to all.

Who is behind the crime?

A more fundamental way is to try replacing the question part with a noun or pronoun. If you can replace a part of the sentence, and the sentence still makes sense, you’ve a declarative sentence containing a noun clause. (This works because a noun clause functions as a noun in a sentence and hence can be replaced by a noun or pronoun.) If you try this test with the above sentence, you can replace the question part in the declarative sentence successfully with, say, He.

He is known to all.

But you’ll struggle to do the same with the question.

Problem #3: Marker words may sometimes be dropped

Few marker words, especially those starting relative clauses, can be left out under certain conditions. So, you may see sentences like these:

Scientists believe Covid is going to stay with us for at least few years.

Don’t ask questions people can’t or don’t want to answer.

Who attended the school I did?

The restaurant we first met in continues to hold special place in my heart.

In the first sentence, you spot the finite verb is going and its subject Covid, but you don’t see any marker word before Covid. Is Covid is going to stay with us for at least few years the second independent clause then?

It’s not because, as you’ll see later in the independent clause section, a second independent clause will be signaled by a coordinating conjunction (FANBOYS) or a semicolon, none of which is present here. It’s a dependent clause with its marker word omitted. Same applies to the other two sentences.

Alternatively, you can follow this quick process.

1. When you see a sentence-like unit (Covid is going to stay with us for at least few years) immediately after a reporting verb (believe), it’s a noun clause with that dropped. Although the list of reporting verbs is long, the common ones are say, tell, mention, believe, reply, ask, know, think, respond, order, admit, deny, and complain.

2. When you see a sentence-like unit (people can’t or don’t want to answer/ I did/ we first met in) immediately after a noun or noun phrase (questions/ school/ The restaurant), it’s a relative clause with its marker word dropped.

The above sentences with their marker words would be:

Scientists believe that Covid is going to stay with us for at least few years.

Don’t ask questions which people can’t or don’t want to answer.

Who attended the school that I did?

The restaurant where we first met continues to hold special place in my heart. [Note that in is missing here. You can learn the rules in the links below.]

Here we covered few cases of omission of marker words. You can cover almost the entire range of such marker words and the conditions under which they’re dropped at these links:

- Marker word that can be left out in noun clauses

- Marker words who, whom, which, and that can be left out in relative clauses

- Marker words when, where, and why can be left out in relative clauses

Participate in a short survey

If you’re a learner or teacher of English language, you can help improve website’s content for the visitors through a short survey.

Problem #4: The marker word may sometimes be preceded by another word

Marker words in relative clauses may sometimes be preceded by quantifiers and prepositions. Even though the clause doesn’t start with a marker word, it’s still a dependent clause. Examples:

Twenty-five applied for the job, three of whom were shortlisted for the interview. [whom is preceded by a ‘quantifier + of’]

It’s difficult to advise a person on a matter in which she is an expert. [which is preceded by the preposition in]

Problem #5: A dependent clause may be nested into another

Most of the examples we’ve seen so far had just one dependent clause, but multiple dependent clauses per sentence are quite common. This sentence, for example, has two.

In today’s meeting, we need to decide whom to promote and whom to counsel for improvement.

They aren’t difficult to spot as long as they’re clearly separated from each other. But only if life was that simple! Dependent clauses can contain other dependent clauses, blurring the lines between them. An example:

This puts me in dilemma because you’re essentially asking who receives the vaccine first.

The sentence above contains two dependent clauses. The clause who receives the vaccine first is contained within (or is part of) the clause because you’re essentially asking who receives the vaccine first. Another example:

It is still not clear when will the new appointment be made or who will be appointed to the post that the management has created recently.

This sentence contains three dependent clauses. The one starting with when is clearly demarcated, but the other two overlap. The clause that the management has created recently is contained within (or is part of) the clause who will be appointed to the post that the management has created recently.

Clauses within clauses! That’s like nesting dolls.

Multiple independent clauses in a sentence, on the other hand, are always demarcated from each other.

How to identify an independent clause?

Like a dependent clause, an independent clause is also a group of words that contains subject-verb combination. However, unlike a dependent clause, it represents a complete idea and hence can stand on its own as a sentence.

Identifying an independent clause is far simpler than identifying a dependent clause. Look for a complete idea containing subject-verb unit. All the three sentences, for example, have one independent clause. (Subject in blue and verb in magenta font.)

The bus stopped.

The college is taking steps to accommodate extra students this year. [to accommodate is a non-finite verb]

In view of the growing number of students seeking admission this year, the college has streamlined its admission process and initiated weekend and evening classes to accommodate extra students. [growing, seeking, and to accommodate are non-finite verbs.]

Even though the third sentence contains two finite verbs, has streamlined and initiated, it contains one independent clause. That’s because both verbs point to one subject, the college, forming one subject-verb unit. (Such sentence is said to have compound predicate.) Two independent clauses must have two separate subject-verb units, like in this sentence.

In view of the growing number of students seeking admission this year, the college has streamlined its admission process, and it has initiated weekend and evening classes to accommodate extra students. [Adding the subject, it, to the earlier sentence creates another independent clause.]

Conversely, two subjects can come together to form a compound subject, but if they point to one verb, the sentence will contain one independent clause.

The dean and the vice dean approved the new admission process. [One subject-verb unit, implying one independent clause]

This sentence though has two independent clauses.

The vice dean approved the new admission process, but the dean approved only after some changes to it. [Two subject-verb units, implying two independent clauses]

Key is number of subject-verb units.

What we just discussed for independent clauses (one vs. two independent clauses) also holds for dependent clauses.

The admission process was annoying because the online application asked for unnecessary information and didn’t allow few common payment methods.

How to identify multiple independent clauses in a sentence?

A sentence can have multiple independent clauses. Unlike multiple dependent clauses though, which can sometimes be nested, independent clauses are clearly demarcated from each other.

You can identify multiple dependent clauses through multiple marker words. How do you identify multiple independent clauses? Multiple independent clauses in a sentence can be identified through presence of coordinating conjunctions (FANBOYS), which is a signal, but not surety, for more than one independent clause.

Ghosts are regular to this building, but no one has seen them. [Two independent clauses]

Ghosts are regular to this building but no other buildings. [One independent clause]

Both the sentences contain but, one of the FANBOYS, but only the first has two independent clauses. If you don’t understand why the first has two and the second has just one independent clause, refer to the post: Is this a simple or compound sentence?

Multiple independent clauses can also be identified through presence of semicolon, which separates independent clauses.

The mob wasn’t just sloganeering; it was intent on stepping beyond to loot and arson. [Two independent clauses]

More examples:

I asked my friend to lower the volume of music he was listening, but he didn’t, so I left the room. [Three independent clauses]

Mac likes to cook; Susan would rather watch TV; I like to solve crossword puzzles. [Three independent clauses]

Compared to identification of dependent clauses, identification of independent clauses faces far fewer issues. Here is one such.

Noun clause and relative clause are generally treated as part of independent clause

Though grammar books differ on this point, noun clause and relative clause are generally treated as part of independent clause. In the first two sentences below, for example, the sentence and the independent clause are one and the same, but in the third, only I resist buying is independent clause.

Where I work out is known to only few. [Noun clause]

Straws which aren’t bent in any direction indicate absence of wind. [Relative clause]

I resist buying unless I’ve cash surplus to pay. [Adverb clause]

Some grammar books treat even the third sentence as an independent clause. Examples in the exercise at the end of the post follows the first convention: Noun and relative clause are part of independent clauses.

Compared to identification of dependent clauses, identification of independent clauses faces far fewer issues. Here is one such.

Problem #1: Imperative sentences are independent clauses

An imperative sentence issues command or makes request. Examples:

Leave now.

Pass the book.

Drop the weapon.

Some doubt that they’re independent clauses because they apparently lack a subject. But imperative sentences contain an implied subject, you. The above sentences are, in fact:

You leave now.

You pass the book

You drop the weapon.

So, this sentence contains two independent clauses.

Leave now, or you’ll miss the train.

Let’s apply what we’ve learnt so far to identify dependent and independent clauses.

Long string of words doesn’t mean more clauses

Both these sentences have just one independent clause, and no dependent clause, even though they differ significantly in length.

The transport department is planning to bring back trains under repair to ease crowding.

Despite opposition from the overworked train drivers, the transport department is planning to bring back trains under repair to ease crowding, a move snowballing into a controversy, with some politicians jumping on to the side of drivers.

And both these have an independent and a dependent clause, with their dependent clauses being poles apart in length.

Studies indicate that none of the explanations account for such rapid transmission of Covid virus.

Studies indicate what works.

Long string of words doesn’t mean more clauses – dependent or independent. What matters is – and we’ve seen this many times before – presence of a pair of subject and verb, and that pair may come in two words (the shortest dependent clause above) or thirty-seven (the longest independent clause above). What makes a clause long is presence of phrases, which unlike clauses don’t have subject-verb combination.

Exercise: Identify dependent and independent clauses

Each sentence that follows has been dissected into its constituent clauses. Subject and verb in each clause, whether dependent or independent, have been highlighted in blue and magenta font, respectively. As mentioned earlier, noun clause and relative clause have been treated as part of independent clause.

1. Whatever you are doing should stop now.

Independent clause: Whatever you are doing should stop now. [Noun clause is part of independent clause]

Dependent clause: Whatever you are doing [Marker word: Whatever]

2. I failed to reach in time because my car ran out of gas.

Independent clause: I failed to reach in time. [Adverb clause is not part of independent clause]

Dependent clause: because my car ran out of gas [Marker word: because]

3. Vaccines that are meant for children are stored in a separate room.

Independent clause: Vaccines that are meant for children are stored in a separate room. [Relative clause is part of independent clause]

Dependent clause: that are meant for children [Marker word: that]

4. Many children in the refugee camp grew up in a world where they don’t know what their lineage is and which place they belong to.

Independent clause: Many children in the refugee camp grew up in a world where they don’t know what their lineage is and which place they belong to.

Dependent clause 1: where they don’t know what their lineage is and which place they belong to [Marker word: where]

This clause itself contains two more marker words, what and which. They too start clauses of their own.

Dependent clause 2: what their lineage is [Marker word: what]

Dependent clause 3: which place they belong to [Marker word: which]

5. She said she won’t attend school tomorrow.

Independent clause: She said she won’t attend school tomorrow.

Dependent clause: she won’t attend school tomorrow [Marker word: none]

There is no marker word here, but there clearly is a sentence-like unit immediately after the verb said. Here, that has been dropped from She said that she won’t attend school tomorrow. Refer to problem #3 discussed in dependent clauses.

6. That type of cancer adversely affects the immune system, forcing it to produce only one type of antibody.

Independent clause: That type of cancer adversely affects the immune system, forcing it to produce only one type of antibody.

Dependent clause: None

The sentence doesn’t contain any dependent clause. That here is a determiner, and not a marker word. Refer to problem #1 discussed in dependent clauses.

If you understand determiners, you can straightaway see that that is not a marker word starting a dependent clause. But if you don’t and you tread on the path of assuming that that is a marker word starting the dependent clause That type of cancer adversely affects the immune system, you can rule it out being a dependent clause by eliminating the possibility of it being any of the three dependent clauses. This is outside the scope of this post, but has been explained in the post on identifying noun, relative, and adverb clauses (linked earlier) through the very same sentence.

7. The process through which they do it depends on the software they use.

Independent clause: The process through which they do it depends on the software they use.

Dependent clause 1: through which they do it [Marker word: which]

Note that the marker word is preceded by a preposition through. Refer to problem #4 discussed in dependent clauses.

Dependent clause 2: they use [Marker word: none]

There is no marker word here, but there clearly is a sentence-like unit immediately after the noun software. Here, that has been dropped from software that they use.

8. If you go after anybody who owned enslaved people or belonged to an organization that was supremacist, then you have to change the name of the Carnegie library. The Washington Post

Independent clause: Then you have to change the name of the Carnegie library.

Dependent clause 1: If you go after anybody who owned enslaved people or belonged to an organization that was supremacist [Marker word: If]

This clause itself contains another group of words starting with who, which in turn contains another group of words starting with that.

Dependent clause 2: who owned enslaved people or belonged to an organization that was supremacist [Marker word: who]

The above clause has a compound verb comprising of owned and belonged.

Dependent clause 3: that was supremacist [Marker word: that]

9. The companies are often accused of putting profit over anything else, but few companies have taken lead in creating employment at places where they work.

Presence of coordinating conjunction but indicates two independent clauses. There indeed are two independent clauses with different subject-verb units.

Independent clause 1: The companies are often accused of putting profit over anything else.

Independent clause 2: Few companies have taken lead in creating employment at places where they work.

Dependent clause: where they work [Marker word: where]

10. The recent audit has pointed out that our problem isn’t lack of technology; the problem is what technology we have deployed.

Presence of semicolon indicates two independent clauses. There indeed are two independent clauses with different subject-verb units.

Independent clause 1: The recent audit has pointed out that our problem isn’t lack of technology.

Independent clause 2: The problem is what technology we have deployed.

Dependent clause 1: that our problem isn’t lack of technology [Marker word: that]

Dependent clause 2: what technology we have deployed [Marker word: what]